Search For Prayer

By Fartun Hassan

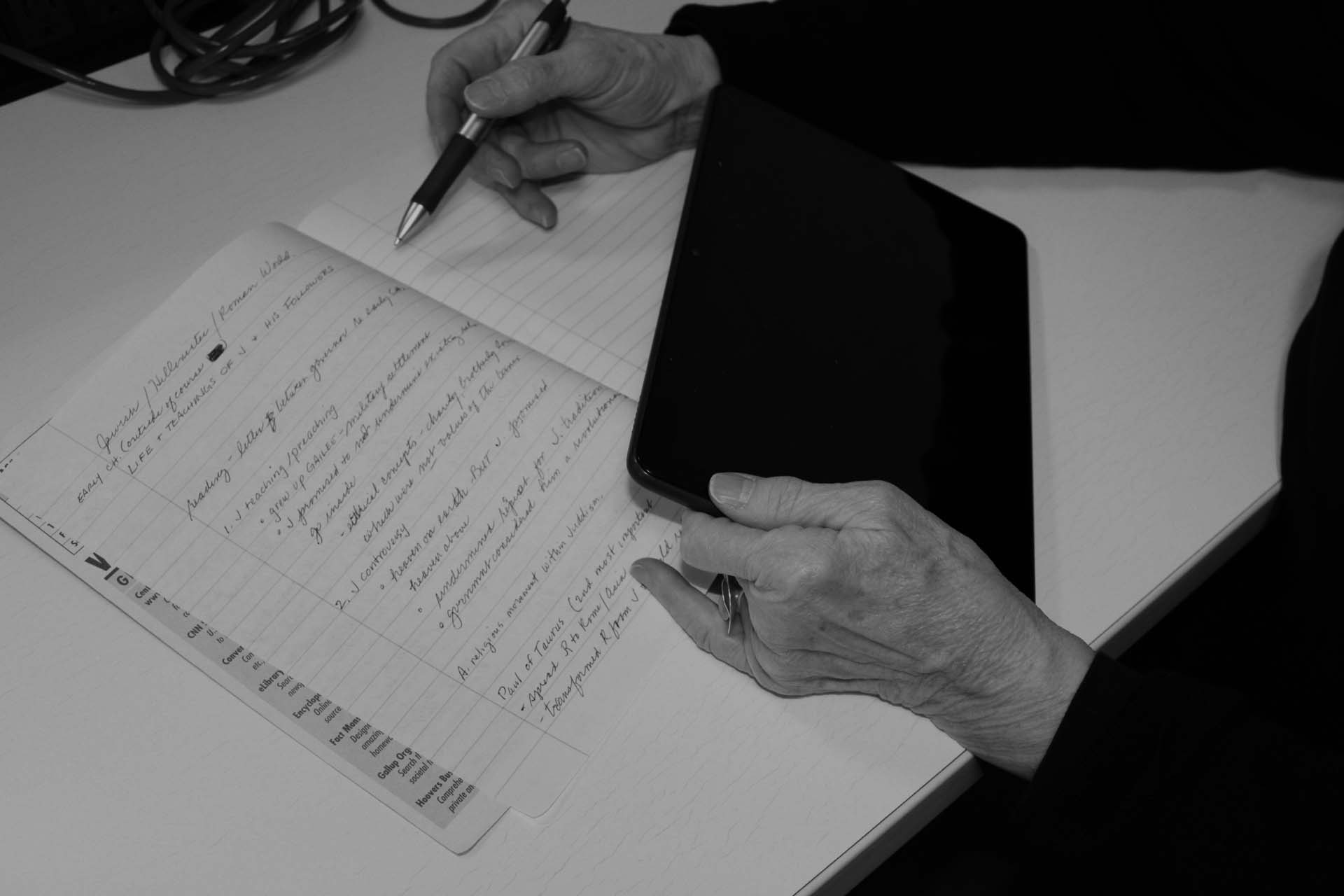

Samia Guled demonstrates making dua, at the Regis Center for Art at the University of Minnesota on March 13, 2024. Photo by Fartun Hassan

“The real issue lies not in the existence of the rooms but in the awareness of their existence.”

“Why do you have your foot in the sink?”

Bismillah. I start the water on my hands. Three times.

“Did you spill something on your shoe?”

I flush my mouth with the water, spit it out and clean over my nose. I begin to wash my face. Three times.

“Are you homeless and taking a bath or something?…”

I raise my sleeves and begin to take turns washing over my right and left arm. Three times.

“Is this…allowed? I feel like I should call security or something?”

In this dimly lit bathroom located in an unassuming corner of one of the oldest buildings on campus, I’m preparing for prayer. Nobody’s asking me these questions. In fact, nobody’s around at all. The questions are the result of the anxious scenario that plays in my head every time I begin the “wudu” process at school. Usually, it plays out like this.

I’m at the very last step of the “wudu”, the washing process Muslims engage in before prayer. Suddenly, someone will walk in. Their shocked face will meet my reflection. I’ll watch their wide eyes gloss over the scene before them. They’ll see a fellow student: One sock in hand, a foot in the sink, shoes off with tissues spread out on the ground below them. I’ll be there, frozen in flamingo position. This will inspire nothing short of a thousand questions in their mind but it’s only silence that will fall between us.

“…”

“…”

I won’t know what to say or where to begin an explanation. They’ll suddenly look away, trying their best to pretend they’re not seeing what they are.

Silently, I’ll finish my process and they’ll hurriedly leave.

To them, this will be the weirdest part of their day, something to mention to their friends or think about on their walk home. To me, they’ll be another face to avoid on campus. Yet for Muslim students at the University of Minnesota, this awkward exchange could happen several times throughout any given day. Like the other students, I don’t have much time to worry about such encounters. The bigger issue is finding a location as the fleeting prayer time approaches.

If at any point so far you’ve related with the wide-eyed bathroom girl, I’ll fill you in on some terms and religious information. Muslims pray five times a day: “Fajir,” right before dawn; “Duhur” around noon; “Asr” sometime in the evening; “Maghrib” at sunset; and lastly “Isha,” the nighttime prayer. These prayer times slightly vary throughout the calendar year. Changes come alongside the seasons and the sun. But regardless of time, unless you’re ill, menstruating or unable in other ways, you are obligated to pray when the call to prayer, the “Athaan,” is called out. Less commonly known is that we first have to be in a state of “wudu” to pray. Its purpose lies in cleansing oneself of any impurities before prayer, similar to wearing clean clothes to Mass or taking a shower before the sabbath. Overall, the “wudu” is a mandatory process one needs to complete before prayer — a process not perfectly catered to a public washroom.

Once I’ve completed “wudu,” I wander the halls looking for a quiet corner to pray. Muslims aren’t allowed to disturb or obstruct others with their prayers. Keeping this in mind, my eyes scour the scenery. I imagine I’m some apex predator armed with eagle-eye vision. Only instead of unassuming prey, I meet the gaze of bored college students looking up from their laptops questioning why I’m inspecting the corners of the study hall.

When I do find a spot to pray, I lay out my prayer mat, which forms a barrier between the floor and where my forehead will rest; that is, if I remember to bring one. Most days, my knee-length jacket doubles as my prayer mat. This isn’t the case for everyone, but when rushing out of my house at 8 a.m. for an 8:30 a.m. lecture, a prayer mat is not the top priority. The prayer process lasts less than five minutes. Once that’s finished, I hurry off to my next class. Depending on my class schedule, I could repeat this cycle once or twice more with “Asr” or “Maghrib.”

In my time at the U, I’ve seen Muslim students praying in hallways, stairwells and parking garages. While that’s my daily experience, is it correct to place that expectation on the thousands of Muslim students who attend the U daily?

The university, aware of its religiously diverse student body, has established mediation rooms throughout the campus. In doing so, the university collaborated with various Muslim representations on campus such as the Muslim Student Association, the Al-Madinah Cultural Center and the Undergraduate Student Government. While these meditation rooms are not in the majority of buildings, they’re decently scattered throughout the campus and open to all religious backgrounds. If you visit Coffman Memorial Union, you’ll also find a spacious room occupied by the various student unions set aside for prayer. These wider spaces allow for the congregational prayer you often see Muslims performing together to happen. Samia Abdulle, a member of the student government says that over the past two years, the university has been working with the students to add more prayer spaces.

For the most part, the situation isn’t bad. But I’d implore you to think again. If there were zero issues in this matter, would it be a common sight to see students scattered into hallways and unassuming corners? The real issue lies not in the existence of the rooms but in the awareness of their existence. Unless you’re writing a story on the matter or making your way to Coffman Hall to ask the MSA yourself, there’s no widely accessible way to know about these rooms. On the official school webpage, besides a mention of the rooms, there are no further details. The link to the single “wudu” location leads back to the same landing page where you began your inquiry. When searching “UMN Prayer Rooms” on Google, you’ll find a Reddit subthread of university students asking around for locations. While their Reddit list is decently sized, it doesn’t cover all of the rooms. Furthermore, even when students are aware of the rooms, they may also find some difficulty getting to the locations.

“I’d say there’s difficulty in my daily life on campus when it comes to prayer. There’s no prayer spaces on the St. Paul campus where I sometimes have class. Also, there’s no spaces in areas like Walter Library where students like me spend a lot of time studying or working. It’s time-consuming having to find some place to pray,” said Bedra Saleban, a Muslim sophomore at the University of Minnesota.

Because Bedra is involved in Muslim student organizations on campus, her go-to is the prayer room at the Al-Madinah Cultural Center located in Coffman Hall. But the university shouldn’t leave it to chance for students to find the prayer rooms. They should be easily accessible, convenient and presented to all students via the official webpage of student cultural affairs.

While I’d never expect protecting students such as Bedra and myself from an awkward bathroom exchange to be at the top of any faculty to-do list, I would expect prioritizing the safety of Muslim students while engaged in the vulnerable prayer process to be. This is especially important as religious hate crimes have increased. It is the responsibility of the university to ensure the safety of all of its students. With these meditation rooms open to all, it is not only Muslim students who benefit. It is my opinion that considering Muslim students only when it’s time for a diversity brochure photo opp isn’t a genuine consideration. While the university has progressed further than the majority of universities of its caliber in this issue, a little push to provide more information on the existing prayer rooms will make a big difference in creating a welcoming campus environment.

It is my hope you’ve learned something while reading this article. A world increasingly divided may only be brought closer by mentally bridging the gaps between us. If you’ve read this article as someone who does not share this struggle, you’ve already taken one step.